Objects, as we know, travel through time. And sometimes monuments or chronicles are not needed: a single line of ink, a signature, a motto slipped into the margin of a book is enough to bring back to the surface, after five centuries, a truth of identity.

In the first part (here), we followed the most cryptic trace: “sans removyr elyzabeth”, written in the Prose Tristan (British Library, Harley MS 49, f.155r), beneath the ex libris of Richard of Gloucester.

A motto that resonates with constancy, memory, unwavering presence, and that likely converses with another mysterious phrase noted on the same folio: “Remember wat yow sayd… A welle forton welle.”

Today, instead, we enter a second manuscript: quieter, more intimate, and perhaps even more revealing.

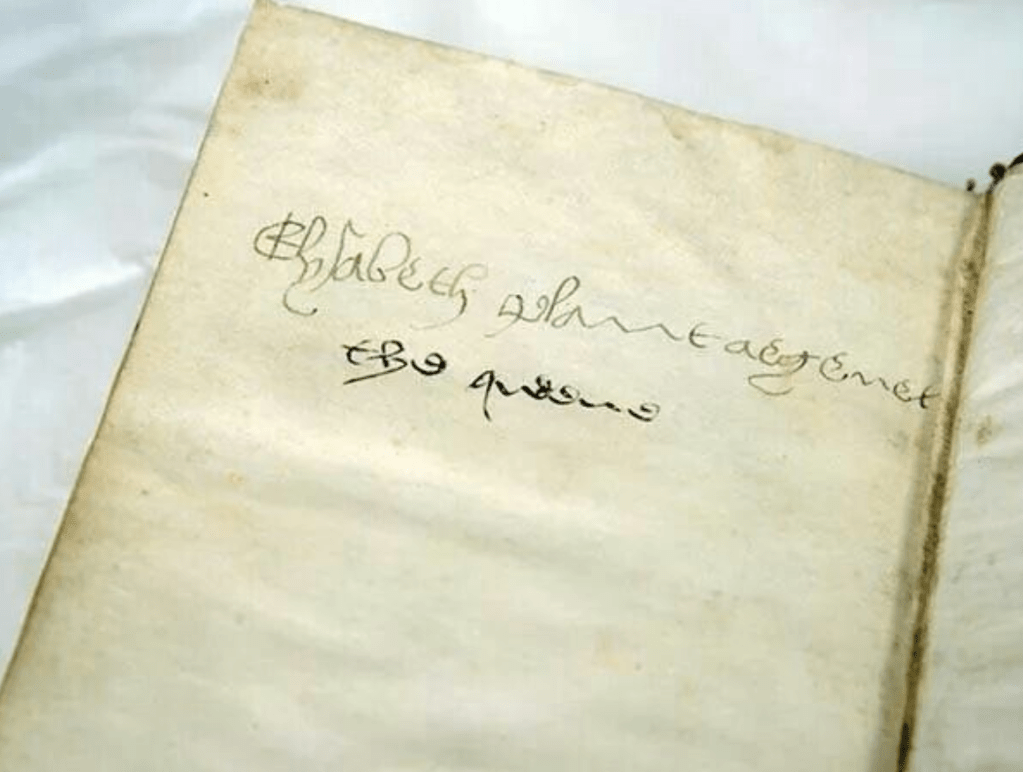

The second book is De Consolatione Philosophiae by Boethius (British Library, Royal MS 20 A xix, f.195r), a text that belonged to Richard III: a classic that every “serious” late-fifteenth-century court owned and read as comfort, moral discipline, and meditation on the caprice of Fortune.

And it is precisely there, after seven blank pages, that a signature appears—one that reads like a declaration:

“Loyaulte me lye elyzabeth”

(“Loyalty binds me, Elizabeth”).

It is an extremely brief phrase, yet extraordinarily dense.

Above all, it is the personal motto of Richard III, Loyaulte me lie, here adopted by Elizabeth and sealed with her name.

This is not a motto that is “hers” in the same way as sans removyr; it is a different gesture: an appropriation, a tribute, and perhaps also a statement of position.

When reading these marks, we must avoid the most common mistake: treating every curve of the pen as scientific proof. Medieval handwriting follows conventions and learned calligraphic forms. That said, some visual details are interesting as narrative clues (not as certainties):

The word loyaulte shows a visible correction on the “y,” added above the line. A gesture that may suggest care: Elizabeth wants that word to be exact, properly written, unambiguous.

The stroke is full and firm: not a casual note, but an intentional mark.

The initial “L” and the “E” of Elyzabeth are more ornate, as if the gesture wished to remain memorable, like a small personal emblem.

The phrase appears compact, almost a single unit: loyaulte me lye does not read as three separate words, but as one body. And immediately after: Elyzabeth.

If sans removyr was an inward promise (perhaps to time, perhaps to herself), here something different seems to happen: loyalty is not a feeling, it is a bond.

And the most powerful element is the syntax itself: loyaulte me lye does not say “I am loyal,” but “I am bound.”

So what is Elizabeth doing here? The question is not “is it romantic?” but “is it identitarian?”

Because a motto can also be a public mask, a political language. And using the king’s motto, then signing one’s name, can mean:

adhering to an order of the world (who is king, who is loyal, who belongs to whom)

declaring an allegiance without stating it openly

– leaving a mark not meant for contemporaries, but for those who would come later.

Read this way, “Loyaulte me lye” becomes almost:

“I am the one who is bound by loyalty. This is who I am.”

It is a sentence that does not ask or negotiate, but establishes.

These book inscriptions, the sans removyr in the Tristan and the loyaulte me lye in the Boethius, are often dated to the period 1484–1485: after the declaration of illegitimacy of Edward IV’s children, and before Elizabeth became a Tudor queen. Not because a date is written beside the signatures, but because the sequence of mottos and historical circumstances makes that time frame the most plausible.

As queen, Elizabeth would in fact use a different formula: “humble et reverente”… more courtly, more domesticated, more aligned with the role to which she was confined.

But now we come to the question that matters most: why mark two such important books in her uncle’s library?

The Prose Tristan was far more than a story: it was a moral universe, a manual of chivalry and, at the same time, a romance of love and destiny. In the medieval world, these dimensions are never truly separate: chivalry lives by values, and values are tested by love, loyalty, and the impossible.

Boethius, by contrast, belongs to another register: the philosophy of downfall and inner redemption. A book in which Fortune is a wheel that lifts and casts down without mercy, and in which the human being must find a fixed point elsewhere.

And here a connection ignites:

in the Tristan appears that phrase about Fortune (A welle forton welle).

In Boethius, Fortune is the central theme.

It is as if, in two different books, the same nerve were vibrating: instability, destiny, the wheel, loss.

So the question is no longer only “why sign them,” but: are they communicating, or communicating with themselves, through these texts?

Is it possible that Elizabeth found in these volumes both consolation and a coded language: a conversation made of mottos, not confessions?

There is also another trace, less often cited but significant. A signature survives on a separate leaf, perhaps from a letter Elizabeth wrote to her mother (British Library, Add. MS 19398, f.35):

“humble et vreye / your loveng dawghter / Elysabeth the quene”

(“humble and true / your loving daughter / Elizabeth the queen”).

That vreye (“true”) strikes me more than anything else. It is not mere modesty: it is a claim to authenticity. Queen and daughter, role and origin, public and private.

And then there is an even rarer choice. In a Book of Hours preserved at Stonyhurst College (Ms. 37), Elizabeth signs herself “Elizabeth Plantagenet – the queen.”

Here she is not simply “queen”: she is queen and Plantagenet. As if to say: yes, I am Tudor by marriage, but York by blood. And that does not disappear.

And then there is the famous letter reported by Sir George Buc (with all the known transmission issues of the text, and the work of modern scholars in distinguishing the original from later intervention). In that account, Elizabeth asks the Duke of Norfolk to intercede with the king on a matter probably related to marriage, and states that she is a “loyal subject in heart, in thought, in body, and in all things.”

But above all, there is the postscript that scandalized many:

“The better part of February is past, and I fear the Queen will never die.”

Read today, it sounds ruthless. Read with the mind of a late-fifteenth-century woman, it sounds above all like urgency. Elizabeth was a pawn: declared illegitimate, politically vulnerable, with the Tudor threat advancing. In that context, “I fear the Queen will never die” may mean: if events do not move, I have no way out.

This is not cynicism… it is survival.

When Anne Neville dies (16 March 1485), Tudor propaganda rushes to build its most poisonous narrative: Richard supposedly eliminated his wife to marry his niece. Richard must publicly deny it, and the political machine reacts.

Elizabeth is sent to Sheriff Hutton along with other young members of the royal family (including Edward of Warwick and John de la Pole). Silence, prayer, waiting. And then Bosworth.

When Richard dies, the possible world that Elizabeth, however she imagined it, was still keeping alive collapses. Shortly afterward, she will be taken to London and married to Henry Tudor.

And now, after this long journey, we reach the point.

The signatures in books tell what propaganda cannot control. Because they are not public speeches: they are marks left where no one is meant to look. And in those marks I see a trajectory:

from “king’s daughter” (received identity),

to sans removyr (constancy as choice),

to loyaulte me lye (loyalty as bond),

to Plantagenet, the queen (integrated, complete, irreducible identity).

In an age in which female identity was imposed as a role, Elizabeth responds with another language: mottos, books, signatures. A form of resistance that makes no noise, but leaves traces.

And if those two volumes, Tristan and Boethius, are truly bound by Fortune and loyalty, then the impression is that of an underground dialogue: not only between Elizabeth and Richard, but between Elizabeth and time itself.

A whisper between the pages that says: “I do not move. I do not forget. I know to whom I am bound.”

Lascia un commento