When the name Heloise is spoken, collective memory almost automatically turns to another figure: Pierre Abélard. Their love story, overwhelming, scandalous, tragic, has, over time, become one of the founding myths of Western romantic imagination. Yet to stop there is to betray precisely what makes Heloise an exceptional figure. For Heloise is not merely the heroine of an unhappy love affair: she is one of the greatest intellectuals of the Middle Ages, a woman who thought desire, knowledge, and female power in an age that made room for none of these things.

Born around 1092, probably into an aristocratic milieu marked by the ambiguity of illegitimacy, Heloise received an education that was extraordinary by any standard. She grew up among books, languages, and study, first in the monastery of Argenteuil and later in Paris, under the guardianship of her uncle Fulbert. In a century in which most women could not read, Heloise mastered Latin, knew Greek and Hebrew, and studied the classics, logic, and rhetoric. She was already renowned for her intelligence when Abélard entered her life: not a tabula rasa to be shaped, but a fully formed mind.

Heloise’s encounter with Abélard was not merely a sentimental affair, but a clash between two intellects. Their relationship began as a philosophical dialogue and soon became a physical passion, lived by Heloise with striking lucidity. In the letters that have come down to us, true masterpieces of introspection, Heloise does something unheard of in her time: she names female desire, analyzes it, and defends it. She does not present herself as a victim, nor as a repentant sinner, but as a conscious subject. She loves Abélard, yes, but rejects the idea that marriage is the only legitimate form of love. For her, marriage is a social institution that diminishes feeling and reduces women to commodities; love, by contrast, is freedom, choice, and mutual responsibility.

The tragedy is well known: a pregnancy, a secret marriage, the brutal revenge of her uncle Fulbert, and the castration of Abélard. It is here that traditional narratives tend to freeze Heloise in the role of the broken woman. In reality, this is precisely the moment when her true career begins. Forced to take the veil against her will, Heloise passes through a phase of profound inner rupture: a nun without vocation, a wife without a husband, an intellectual reduced to silence. But she does not remain there.

To reduce Heloise to her love story with Abélard is to ignore the arena in which her intelligence had its greatest impact: the concrete governance of a female community. When Abélard entrusted her with the leadership of the Abbey of the Paraclete, Heloise became an extraordinary leader. She was abbess, administrator, reformer. She did not merely run a monastery, she reinvented its very model.

Her most radical choice was also her most revolutionary: to write a monastic rule for women starting from women’s bodies. Heloise grasped a truth that monastic tradition had consistently ignored: the available rules, especially the Benedictine Rule, were designed for male bodies. For monks who did not menstruate, give birth, experience hormonal cycles, gynecological illnesses, pregnancy, or the physical consequences of undernourishment in biologically different bodies. Heloise’s brilliance lay precisely in her refusal to accept that women should simply “adapt” to a model never designed for them.

In her writings and in her requests to Abélard, often dismissed by later historiography as purely theological questions, Heloise raised issues that no one before her had dared to articulate systematically:

how can a rule ignore the cyclical vulnerability of the female body?

how can rigid fasting be reconciled with heavy menstruation, anemia, physical weakness?

what sense is there in imposing identical penances on those who live radically different bodily experiences?

Heloise speaks openly of sanguis mulierum, the blood of women, not as symbolic impurity, but as a concrete biological fact. In an age in which menstrual blood was burdened with taboo, fear, and superstition, she returned it to the realm of practical responsibility. An abbess, she argued, must govern real bodies, not spiritual abstractions. For this reason, she called for, and largely obtained, a mitigation of the most extreme ascetic practices. Fasts were adapted, penances differentiated, and the organization of labor took physical strength into account. Illness was no longer interpreted as moral fault, but as a condition to be managed.

Heloise did not reject asceticism; she made it sustainable, and above all, non-punitive. Here lies a profoundly modern vision: Heloise separated spirituality from the mortification of the body. She did not believe holiness necessarily passed through physical suffering. On the contrary, she intuited that a spirituality which ignores the body produces only guilt, hypocrisy, or destruction. It is an intuition that anticipates by centuries feminist thought on the body as a site of knowledge.

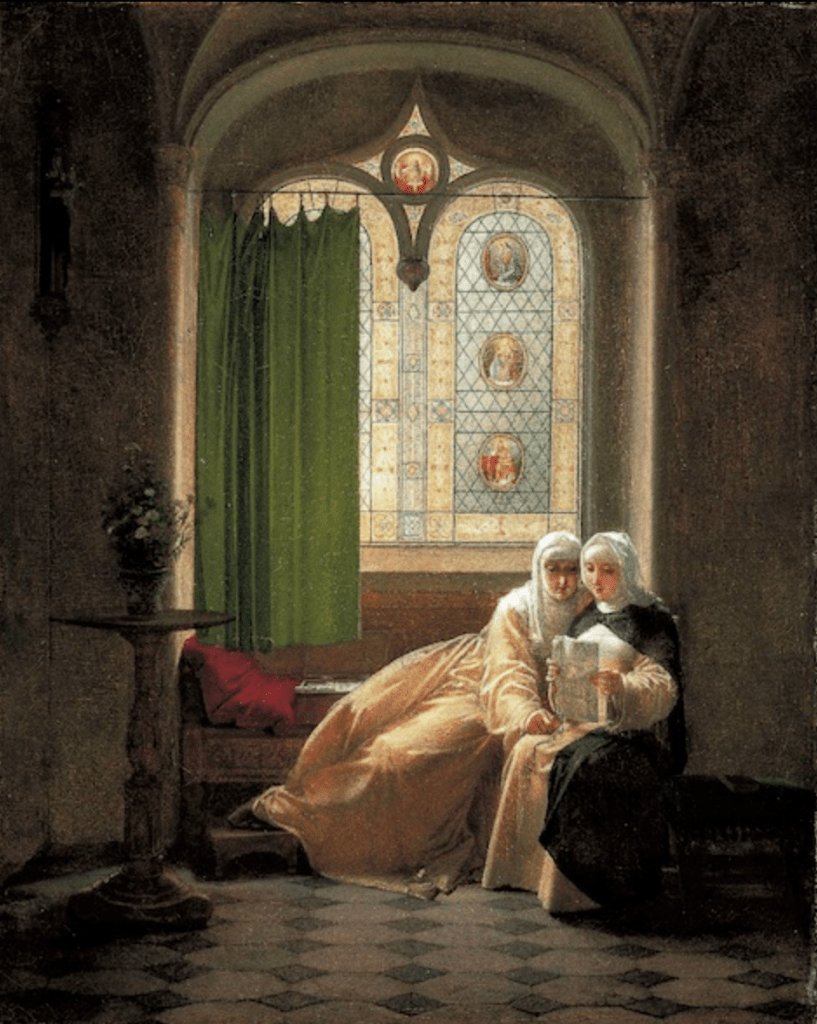

Alongside this embodied reform, Heloise also transformed the intellectual life of the monastery. At the Paraclete, one studied, wrote, and sang. Sacred music, also thanks to Abélard’s compositions, became an integral part of education. The nuns were not encouraged toward total silence, but toward disciplined thought. Heloise defended the idea that women could understand Scripture, discuss it, interrogate it. She did not want mute mystics, but thinking women.

In the Problemata Heloissae, her intellectual stature emerges in full: Heloise raises problems of moral theology, biblical interpretation, and doctrinal coherence. She asks, questions, demands answers. She does not accept authority simply because it is authority. Hers is a leadership grounded in word and reason, not blind obedience. In this sense, Heloise appears strikingly modern: she believed that thought is a moral act, and that individual conscience counts as much as law.

Even in her later letters, when myth would have her finally pacified, Heloise remains restless and lucid. She does not renounce the past, nor does she rewrite desire as youthful error. She writes a sentence that still disarms today with its honesty: I would rather have been your lover than your wife. It is a declaration that overturns centuries of patriarchal morality and renders Heloise a solitary and powerful voice in the Christian Middle Ages.

In this sense, Heloise was also an uncomfortable figure for the reformed Church of the twelfth century. Her model of a female abbey, cultivated, autonomous, embodied, would not be replicated. In the centuries that followed, another paradigm would prevail: the mystical woman, visionary, often suffering, often ill, often silent. Heloise, by contrast, was healthy, lucid, rational, and perhaps for this very reason less “usable” as an edifying model.

When she died in 1164, Heloise left behind not only a love story, but an extraordinary political and spiritual experiment: a place where women governed themselves without denying their own physicality. Perhaps this is why later memory preferred to transform her into a romantic legend. Passion is easier to narrate than power.

To reread Heloise today is a necessary operation: to lift the veil of myth and restore dignity to the abbess. To a woman who dared to say that faith does not require hatred of the body, and that thought is not a male prerogative. In a Middle Ages that believed it could control women through rule, Heloise answered with the only true revolution possible: writing the rule starting from herself.

Lascia un commento