Objects, as we know, travel through time. They retain something of us, something we chose to imprint so that our children, our grandchildren, and all those who come after us might understand who we truly were.

Sometimes a single book, a line, a signature, a motto… is enough to cry out to the world, centuries later, who we were and who we still are, if only in the memory of those who encounter us.

Elizabeth of York, mother of Henry VIII, did exactly this.

At the court of King Richard III, Elizabeth had access to her uncle’s library.

And in those books she left several indelible traces. In this first part, we will look at the most mysterious and cryptic of them all.

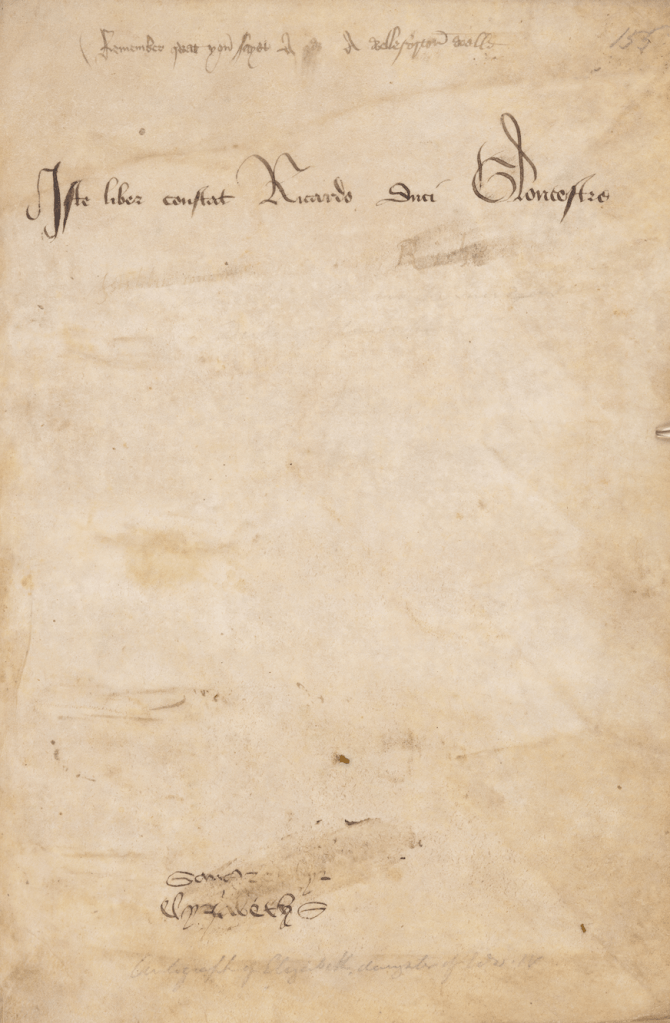

We find it in the Prose Tristan, a book owned and signed by Richard with the note: “This book belongs to Richard, Duke of Gloucester” (British Library, Harley MS 49, f.155r).

Beneath her uncle’s ex libris, Elizabeth signs for the first time with what appears to be her personal motto: “sans removyr elyzabeth”.

The expression, in Middle French, means “forever, with constancy” (cf. DMF, s.v. mouvoir) and derives from the older formula sans mouvoir / sans partir ne mouvoir, which indicated an unwavering, steadfast feeling—“forever, unchangingly.” This is attested in several passages by Machaut:

“Si l’ameray, sans partir ne mouvoir,

De cuer, de corps, de penser, de pouoir,

Tout mon vivant…” (Les dames, 1377, 34*)

(I will love her, without leaving or wavering, with heart, body, thought and all my strength, for all my life…)

“…Et qu’aveuc li demeurent, sans mouvoir,

Mon cuer, m’amour, ma joie et mon espoir.” (Les dames, 1377, 93*)

(…And may my heart, my love, my joy and my hope remain with her, without changing.)

“…Quant ma cure

En si plaisant creature

Est sans partir ne mouvoir.” (Les lays, 1377, 332*)

(…For my desire, in so pleasing a creature, does not leave nor change.)

Because of this, beyond the intuitive translations (“without changing,” “without forgetting”), the motto is best understood as a declaration of constancy, inner loyalty, and unwavering presence.

Elizabeth read that book, loved it, and marked it as if to say: “I am here, I am in these pages, I will never change, I do not forget.”

The inclination of her writing is very vertical, almost restrained, with some letters leaning slightly to the left. This suggests strong self-control, emotional reserve, and a desire not to expose herself too much… even when she is expressing something intimate.

The pressure is moderate yet firm, with clearly marked strokes (especially in the “z” of elyzabeth).

It denotes self-awareness and a need to give weight to what she writes. Every letter seems “asserted.”

The initial “s” is very open, while the final “r” in removyr rises in an upward curl: a sign of thought returning, cyclical memory, inner recall.

The “z” in elyzabeth is particularly rich, well-shaped, almost decorative: a hint of personal pride, or a desire to leave a recognizable mark.

The final “th” is tightly linked and closed, almost a knot: a gesture of protection, closure, preservation.

Her handwriting is compact, not expansive, slightly compressed in width: someone who holds herself back, measures, reflects before acting.

The words are clearly separated, but sans removyr appears as a single inseparable formula, a unit of meaning and identity.

It is a declaration of identity anchored in memory, perhaps addressed to time, to someone, or to herself: as if, by writing it, Elizabeth were fixing her being amid chaos.

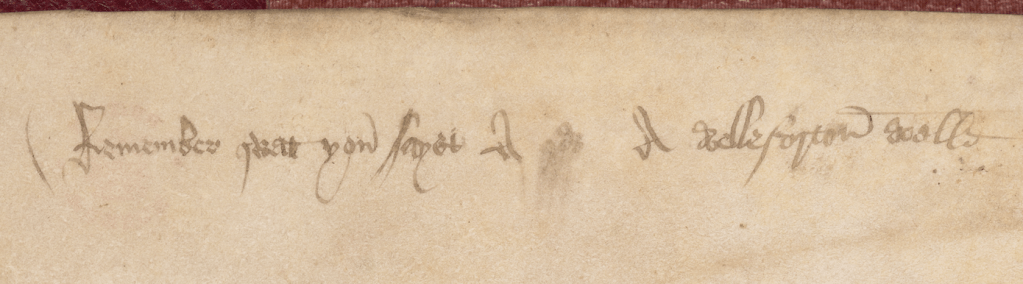

Curiously, above Richard’s ex libris appears another enigmatic phrase: “Remember wat yow sayd A… A welle forton welle.”

(“Remember what you said, good fortune”)

Several historians agree that the handwriting is contemporary with Richard’s and was probably written by him, though it is difficult to determine when, why, or for whom.

This motto of Elizabeth’s is, in my opinion, the one that defines her the most. At that time, Elizabeth was no longer a princess, because she had been declared illegitimate by Parliament after it emerged that her father, Edward IV, had married her mother, Elizabeth Woodville, in a second, and therefore invalid, marriage while already pre-contracted to another woman.

But it was not her only motto. Before this one, she had a simpler and emblematic signature: “the king’s daughter.”

Elizabeth spent her days reading, making music and embroidering. She loved books from childhood and signed nearly all of her volumes. The first signature we find is in the History of the Holy Grail (British Library, Royal 14 E III, f. 1r), where it reads:

“Elyzabeth the king’s daughter.”

It is a childish yet aware handwriting: “I am the king’s daughter.”

The writing leans gently to the right, a sign of an emotionally expressive and relational temperament, but not impulsive.

There is no excess of slant: it is soft, controlled… typical of someone who feels deeply but holds back.

The “e” and “a” are open: signs of receptivity, curiosity, and honest expression.

The final letters have wide but unfinished loops: thoughts held back, feelings half-revealed, a sense of incompleteness.

The baseline is not perfectly straight, hinting at emotional sensitivity, easily influenced by environment and mood.

The letters are rather separate, not connected by a single flowing line: a mind that reflects, weighs, does not give itself away easily.

The handwriting is medium-sized but tends to narrow toward the end… a sign of a person naturally inclined to openness, yet constrained by circumstance into reserve: duty, humility, prudence.

The pressure is light to medium-light, perhaps also due to the wear of time, but it suggests a non-aggressive, delicate hand. Considering she was still a child, it may simply reflect uncertainty: a reflective personality inclined to internalize.

Another significant example appears in the manuscript Garrett MS 168. The manuscript was written and decorated in Bruges after 12 September 1481, then rebound at Westminster by the famous “Caxton Binder.” It was made for Edward, Prince of Wales, Elizabeth’s brother and future (if only for a very short time) King Edward V.

In those pages, alongside Elizabeth’s signature (“Elysabeth the kyngys dowghter boke”), we find that of her sister Cecily (“Cecyl the kyngys dowghter”).

A gesture of affection, perhaps, but also of identity and resistance: imprinting her name in a book made for the heir to the throne is a silent yet powerful act of self-affirmation.

The pressure here is strong and steady: a sign of will, determination, firmness.

Elizabeth feels both the right and the duty of what she declares. The act of writing is not hesitant: it asserts a presence.

The letters are slightly inclined to the right: emotional openness, engagement, inclination toward connection.

The “z” of Elyzabeth has a distinctive, almost Gothic elegance… refined yet firm.

The “g,” “h,” and “k” (in kyngys, dowghter, boke) are wide, curved, well-defined: inner strength, independence, a desire for personal expression.

The capitals (“E” in Elyzabeth and “K” in Kyngys) are tall but stable: awareness of status.

The words are clearly separated, balanced between gesture and meaning: a sign of clarity, self-control, inner order.

The writing does not rush: it anchors itself to the line, coherent and disciplined.

The letters are medium-sized, with ample descenders: a personality externally restrained but inwardly deep.

Unlike the first signature, timid and childish, here Elizabeth seems to have found a steadier, more confident voice… perhaps emotional growth, or a different phase of life.

This signature is a true act of identity: Elizabeth signs a book as her own, fully aware of her role (“the king’s daughter”), yet without ostentation.

It is a gesture both strong and elegant…quietly authoritative.

Here emerges a young woman fully aware of her worth and her place, yet never arrogant: moving between loyalty, introspection and contained strength.

And here, Elizabeth was only sixteen.

These are just two of the mottos and signatures used by Elizabeth of York, from childhood to her years at the court of King Richard III.

But during that period something else happened: Elizabeth adopted another motto—not originally hers, but rather a tribute of loyalty and closeness to someone who meant something important to her.

…But we will speak about this in the second part here

Lascia un commento