If today a doctor told you, “To understand what’s wrong with you, let me examine your urine… under the light of the Moon,” you would probably run for your life. In the Middle Ages, however, not only would you not have been scandalised… you would have considered the request perfectly normal.

For centuries, in fact, the most serious, scientific, and reliable method for diagnosing almost anything (from gout to melancholy) was to analyse urine inside an elegant glass vessel called a matula. Yes, basically like now… more or less.

Medieval medicine was deeply convinced that urine held a faithful reflection of the entire human body, and that simply looking at its colour would have been far too easy, almost trivial. One had to observe it as a whole, examining the liquid in natural light, lifting the vessel exactly the way a sommelier lifts a glass of wine (a lovely image, isn’t it?).

And as the light filtered through the glass, the physician evaluated the shade, the texture, the sediments, the foam, the smell and, in the most extreme cases, even the flavour (yes… also fun to imagine).

But even all this wasn’t enough. The final interpretation had to be compared with what was happening in the heavens: the position of the planets, the lunar phase, the balance of the humours. If Mars happened to be in a hostile aspect and the urine leaned towards red, poison was suspected. If a waning Moon was paired with urine that looked too pale, one spoke of “weakness of the cold limbs.” And if the urine turned green, the doctor would lower his gaze with the sort of delicate solemnity reserved for the worst omens… and you knew you were already done for.

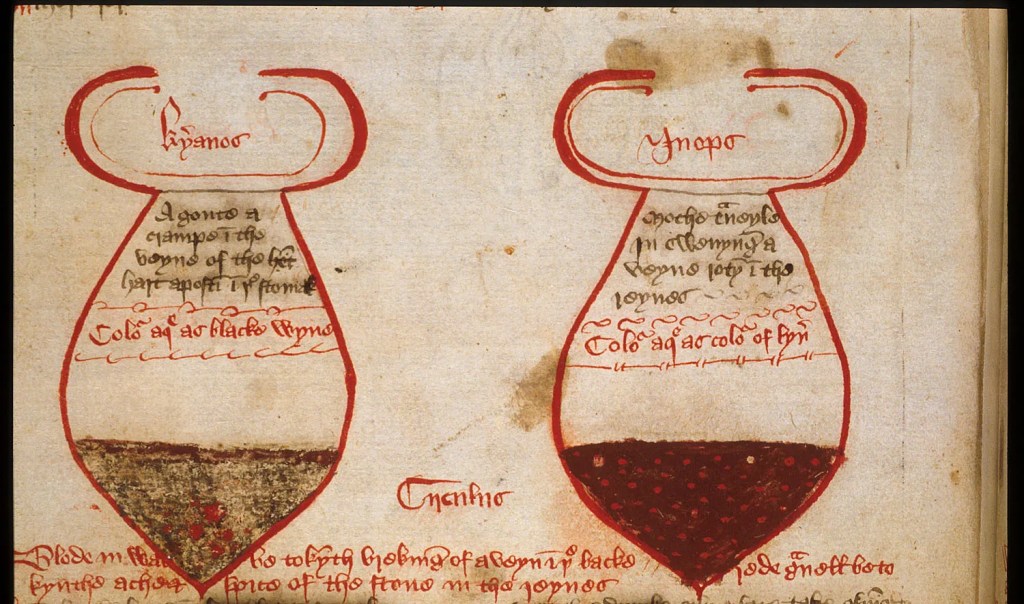

This entire pseudo-cosmic choreography may sound strange to us, but for them it was solid science (and to be fair… they weren’t completely wrong). Some physicians even carried around colour charts, small illustrated wheels showing every possible shade of urine and its supposed clinical meaning. A kind of medieval Pantone.

One of the most famous works on this topic is On Urines, written at the beginning of the 13th century by the physician Giles Corbeil. It was essentially a practical manual for anyone who wanted to become an “expert judge of urine,” and it began by reminding readers that a proper diagnosis required obsessive attention to variables such as age, sex, constitution, habits, diet, emotions, exercise, and even the use of ointments and baths. But above all things, one had to observe the urine with a clinical eye. His descriptions are extraordinary:

White, thin urine? Then one could suspect dropsy, intoxication, diabetes, rheumatism or delirium.

Livid urine? The terrible sign of a mortifying limb or some rebellious internal humour.

Wine-coloured urine? Possible continuous fever, rupture of the renal vein or, alternatively, an excess of sex or dancing.

Urine with a mucous appearance? In men, a sign of gout; in women, probable pregnancy.

What is even more surprising, however, is discovering how widespread this subject was outside elite medical circles. There are, in fact, more than two hundred and ten manuscripts in Middle English devoted exclusively to the art of DIY urine analysis. It was a full-blown editorial craze: the Middle Ages’ own “how-to” guides, little handbooks created for practitioners, midwives, self-taught healers and even ordinary people who wanted to understand what was happening inside their bodies. Some texts were so short and direct they resembled pocket reminders, quick lists of symptoms and interpretations, almost cheat sheets to help people navigate the complex art of diagnosis.

Special attention was given to women’s health, which often occupied entire sections. According to these treatises, a woman’s urine could reveal whether she was a virgin, whether she had engaged in sexual activity recently, or whether she was pregnant.

So why remember all this today? Because it’s one of the most fascinating examples of medieval mentality, that strange blend of naivety and intuition, superstition and observation, imagination and science. When we picture medieval people as ignorant, crude, dirty or prudish, we forget they were desperately trying to understand a body they were not allowed to dissect (officially), analyse or X-ray. And so, to read themselves from within, they had no mirror more accessible than urine: that small pool of colour that carried the echo of an inner mystery.

And, if you think about it, we are not so different. We may no longer lift a matula towards the light of Mars, but how many times, in the dead of night, do we search for symptoms on Google hoping we’re not at death’s door?

Lascia un commento